I have a new good companion which I met for the first time a month ago. It all started with the Klack keyboard noise simulator I had installed on my Apple Studio computer. My subsequent musing, Klack Goes the Keyboard, proved to be more popular than many of our regular posts. It’s pure nostalgia in a bottle, of course, but it caused me to dust off all my old typewriters and indulge in some real clack-clacking.

The next happening was totally unpredictable and took me down a veritable rabbit hole. You know, you look for something on YouTube and within minutes you’ve scurried down some bunny thoroughfare that you never imagined existed.

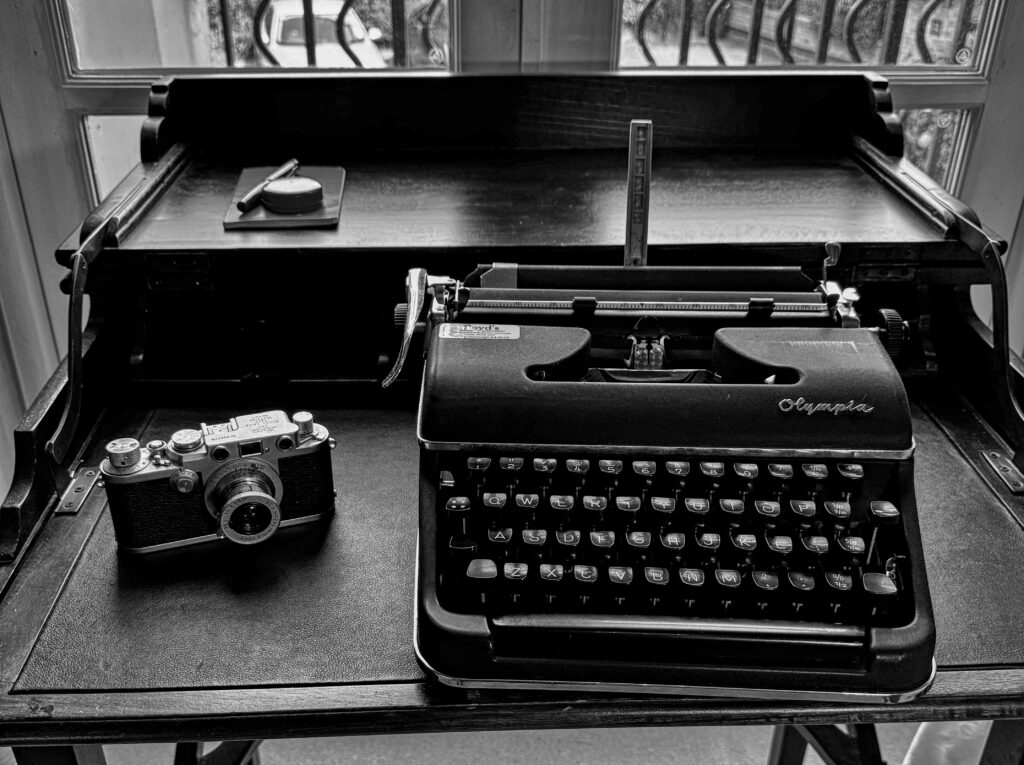

So it was with the typewriter article. As a direct result of publishing the piece, I was soon in touch with a remarkable man, John Tanner, “The Retired Typewriters Expert”. John is a noted typewriter repairer and seller, based high up in south-east London, not a stone’s throw from the Royal Observatory and the Meridian. Time starts there. I decided to take one of my typewriters, an Olympia SM2 from the early 1950s, to John for fettling. The carriage was locked solid.

First temptation: The Good Companion and the Leica Model I

Off to the eastern hemisphere on an important quest

This part of London is quite a trek from where I live in the western suburbs, and involved a bus, a Tube and a train, not to mention 90 minutes of my day just for the outward journey. I packed the Olympia SM2 (why do I now always want to call it an Olympus?) in a duffel bag and prepared to hop across the Meridian from the western to the eastern hemisphere. Perhaps, I thought, the ley lines thought to lie thereabouts would free up the carriage. No such luck.

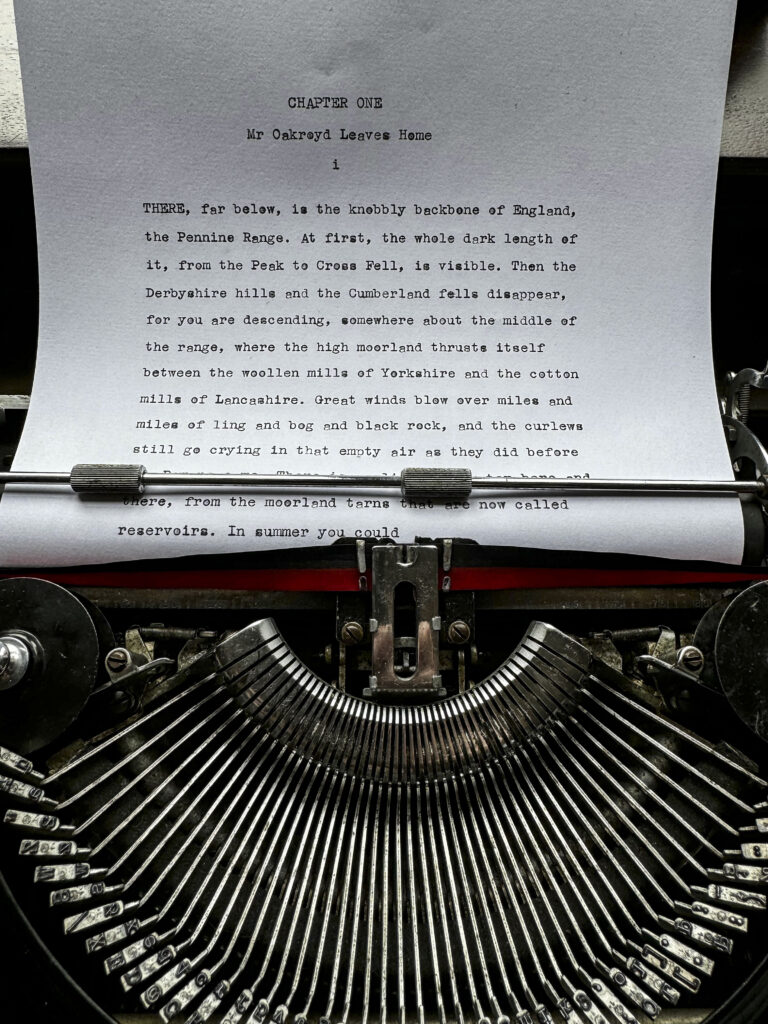

As I unpacked the Olympia in John’s workshop, I noticed his display of vintage typewriters, all of which were for sale. This was Temptation writ large. And when I saw the Imperial Good Companion, glistening in its coat of black paint and resplendent with gold transfers and, even, a royal warrant, it was love a first sight. I just had to have this wonderful example of 1930s writing excellence.

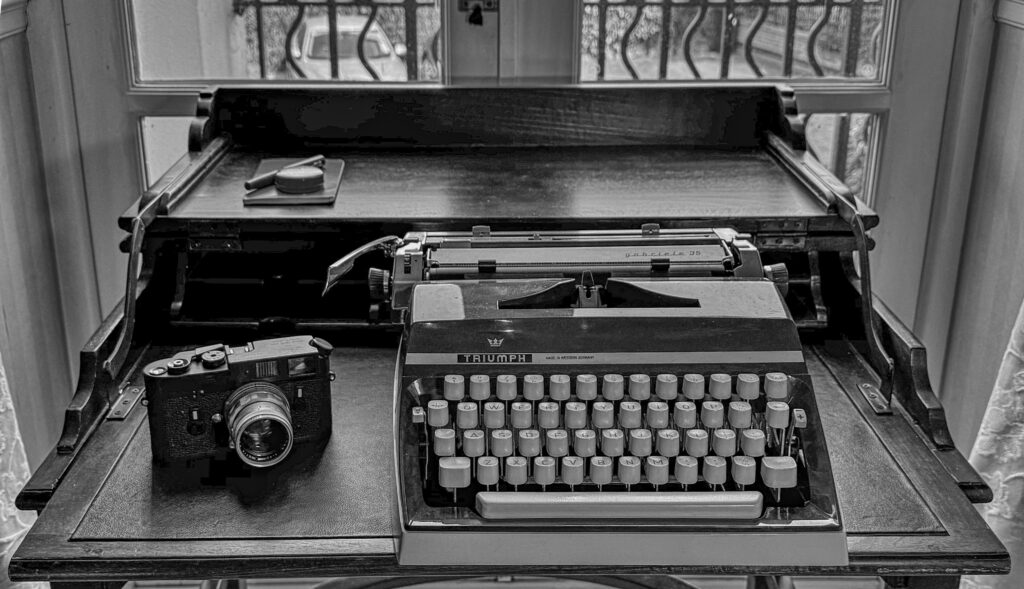

In a buying mood by then, I also carried away1Sharp-eyed readers will recall I travelled by public transport. In fact, I went back a week later in my car to collect all those machines a 1930s German Olympia Progress (a forerunner of the broken SM2) and an altogether more competent and “modern” Triumph-Adler Gabriele 35 from the early 1970s. Where would I put them all? As you see from the earlier article, my shelves are already bursting with vintage portables.

But the Imperial Good Companion is (as they say in the 21st Century) Something Else. It is The One (as they said in the 1920s). This is the most delicious of portables, beloved of authors in the thirties and forties and even owned by King George V (hence the warrant, proudly fixed to the front of the machine).

Indeed, this is a machine with a particularly fascinating history. Why is it called The Good Companion, for instance? And why was it such a success in a period when good portable typewriters were legion?

Enter J.B. Priestley

The answer is one particular author, John Boynton Priestley, who was born in Bradford in 1894 and died in 1984 in Stratford-upon-Avon. Immensely popular in the middle of the last century, Priestley is acknowledged as one of the foremost English novelists. Sadly, he has been all but forgotten and is definitely unfashionable. This is a great pity, as you will discover if you venture to read one of his novels.

In 1931, when the original Good Companion model was constructed in the Imperial Typewriter Company’s Leicester factory, J.B. Priestley was already famous. Everyone knew his name, and his latest books, such as Angel Pavement and The Good Companions, were runaway successes. The first film version of The Good Companions in 1933 (and I think the best) played to packed houses. If you have an hour or so to spend, you can watch it at the link below.

In a touch of modern marketing, Imperial managed to persuade Priestley to sponsor the new design, and it promptly became “The Good Companion”. Rumour has it that the great man preferred to use a Royal, but this did nothing to tarnish Imperial’s success in selling this little marvel.

Modifications to the Companion

My particular Good Companion was made in 1940, at the start of the war, and has been subject to an interesting modification.

As with Leica cameras and lenses, there are databases to track the date of manufacture of most typewriters, so I know it was manufactured during the first full year of hostilities — about the same time as the Olympia Progress was being finished by the enemy (see picture below).

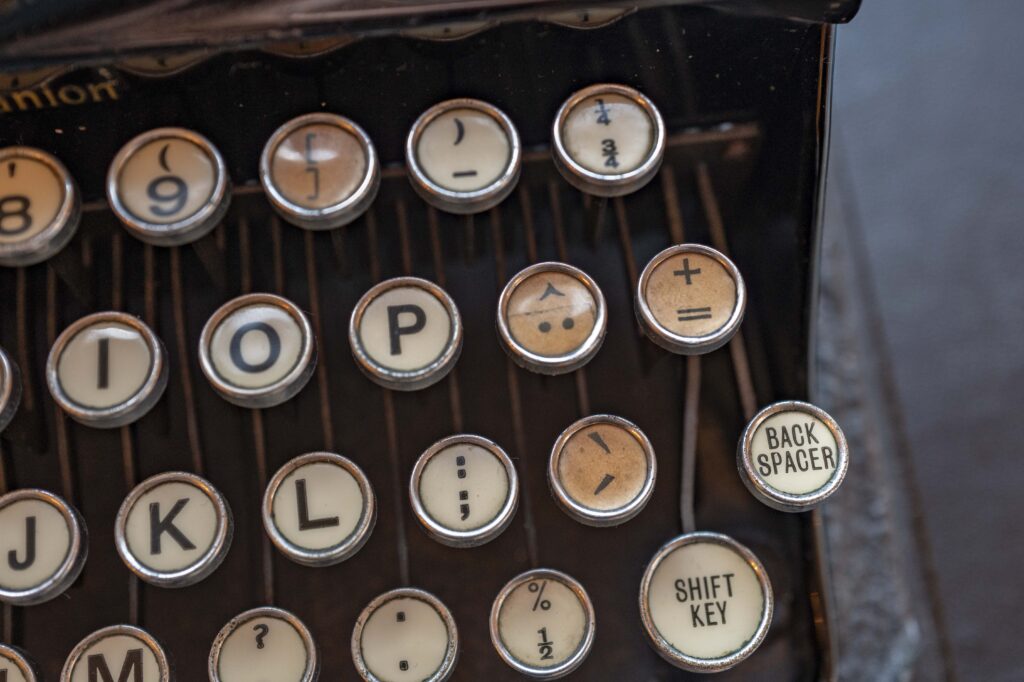

Four type bars and keys have been changed — the yellowing key tops compared with their white companions are the giveaway. My Companion has square brackets (very useful in our “modern” computer age), a plus and equals key and two accent keys covering circumflex (û), acute (é), grave (à) and Umlaut (ä).

The two accent keys are “dead” in the sense that they do not move the carriage. You type the accent followed immediately by the vowel and only then does the carriage advance. This was a common feature of most typewriters.

These enhancements are unusual for an English typewriter keyboard and indicate that this particular machine must have been used for writing in French, German and, possibly, other foreign languages. It has led me to some speculation, since my Good Companion was born during a world war and might have been involved in some hush-hush typing. Could it have been used in Bletchley Park?

Unqualified success

My new BTF (Best Typewriter Friend) is a delight to use and has given me more pleasure in the past month than I would have thought possible. The output is no great shakes, nothing to compare with, say, that from later machines such as those from Olympus, Adler and Triumph, but it has its charm.

I particularly appreciate the old-fashioned curly numbers and the wonderful fractions. The machine is in first-class condition for its age, apart from obvious wear on the wooden, leatherette-covered tray to which it is attached. This tray forms the bottom of the case when the lid is attached. While the bottom board can be removed by unscrewing the feet of the typewriter, I suspect it might not go together again perfectly, and this would be an act of vandalism.

My Good Companion is thus an unqualified success and occupies pride of place on the typewriter shelf in my study. However, it is not just the little portable that has fired my imagination and kept me so busy over the past month. Thanks to the Good Companion, I have been wandering down English country lanes, sampling theatre performances in grimy northern towns and striding down a dingy City of London cul-de-sac known as Angel Pavement, not far from Red Dot Cameras in 2024.

I have rediscovered the J.B. Priestley of 1929, and I cannot imagine why I have neglected him for so many years.

View from the gods

In his day, Priestley was looked down upon by more cerebral authors, by the Bloomsbury Set, and not least by Virginia Woolf and Evelyn Waugh. Priestley was accused of pandering to the middle classes (how awful!), but his many novels were immensely successful. Graham Greene dismissed Priestley, on the evidence of the recently published Angel Pavement, as a fourth-rate Dickensian with the tart: “Sold a hundred thousand copies… two hundred characters. Enough said.”

I suppose that any book that is so popular can be accused of being “common” by those who set themselves up as the arbiters of taste, peering down from the gods. But, as Lee Hanson of the J.B. Priestley Society suggested, “Anyone who has stayed away from the novels of J.B. Priestley, or has been put off reading him, has been missing out on one of the wisest, most nourishing, most readable and most talented authors of the last century”.

Second temptation: The Olympia Progress and the Leica III

Dickensian fluency

Many, many years ago, I devoured most of Priestley’s 30-odd novels. Despite this, I have given him little attention in the past 40 years. This is a great shame, for it took my Good Companion typewriter to prompt me to re-read the eponymous novel. As is often the case when revisiting an old favourite after several decades, I remembered little about it, apart from it having something to do with a travelling theatre troupe.

But what a delight. I had forgotten Priestley’s storytelling abilities, his almost Dickensian fluency in devising names that reflect the character and quirks of their owners, his wealth of social detail, his preference for sympathetic characterisation which encourages us to bond with the George Smeeths, the Jerry Jerninghams, the Inigo Jollifants, and the Harold Turgises of the early novels. There are few real rotters in Priestley’s early novels. Even the villains are portrayed sympathetically.

Cook arrived with the coffee, and put down the tray with the air of a camel exhibiting the last straw.

— Angel Pavement

The price of everything…

The amount of detail on prices in Priestley’s novels is astonishing. I find this hugely fascinating, both in judging relative prices and in fully understanding the ramifications of inflation over the century. It is a subject that has always fascinated me, and I have lived through a period when £3 a week was a good starting wage for a young clerk.

It was Saturday morning; he had just received his fortnight’s pay, six pound notes, one ten shilling note, and two florins.

— Mr Turgis, Angel Pavement

Priestley gives us the cost of everything while underlining the value of everything2To paraphrase Oscar Wilde, some people know the price of everything and the value of nothing. Written in 1892, the phrase is still very relevant today. Value is subjective whilst the price of a product is generally the same for everyone.. The British pound has lost 99 percent of its value in the past 100 years, and the same can be said for most currencies. But what was it like to live on £1.10s or £3 a week in 1929? What could you buy? The amount of social detail embraced in these figures is staggering.

By lunchtime she felt so discontented that, instead of spending the usual ninepence or so at the little teashop not far away, she went further afield, to a superior place just off Cannon Street, and had a cutlet and peas, apple tart and cream, and a cup of coffee, paying her half-crown manfully

— Miss Matfield, Angel Pavement

… and the value of everything

George Smeeth, the steady-as-he-goes head clerk in Twigg & Dersingham’s office on Angel Pavement, received a rise of £1 a week, taking his pay up to a heady £7 4s., on which he supported his wife and two teenage progeny. This extra quid was the cause of major strife in the Smeeth household. Cautious George, determined to put such a large sum aside for future needs, was overruled by Edie, his spendthrift wife, who promptly incurred a liability of £3.10s which nearly bankrupted the family.

My Good Companion typewriter would have cost £14 when it was launched in the early 1930s. That represents two weeks’ wages for Mr Smeeth, equivalent to nearly £900 today. Interestingly, this is only slightly less than the cost of a Leica Model I at the time (see the above photograph).

An old flame: The Olympia SM2 and the Leica IIIf

Old acquaintances

I now understand why I was so enthusiastic when I read The Good Companions in my early twenties. In recompense for decades-long neglect, I am currently reacquainting myself with the denizens of the dreary office on Angel Pavement, having just last week taken my leave of the good companions. I’ve given myself a new literary target, to polish off as many Priestley novels as I possibly can during the coming summer.

Few novels can transport you back to an earlier era with such accuracy and wealth of detail as can these early works. Both Angel Pavement and The Good Companions were exceedingly modern in their day — Priestley frequently refers to “modern” and succeeds in encouraging us to look at 1929 as a modern era, rather than a year from the dim past.

Modern readers (if we regard modern as being 2024 as Priestley regarded it as being 1929 when he wrote The Good Companions; some people apparently believe that “modern” is only now and has never been before) will find the novels entirely devoid of political correctness. Which is not surprising, since no one had thought of it.

The companion in newfangled colour

Principles

Jack Priestley was a noted socialist and staunch supporter of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in the late fifties and early sixties. George Orwell, probably wrongly, believed that Priestley was a communist. JBP stuck to his principles in refusing both a knighthood and a peerage, yet taking inordinate delight in being awarded the Freedom of Bradford, the Bruddesford of his novels. The city is evoked in all its grime and inner beauty in the semi-autobiographical novel Bright Day, first published in 1946.

Some attitudes and nomenclature in Priestley’s novels will shock the sensitive youth of today. However, I value his novels as a social record of the times. They might not pass through the colander of “modern” social arbiters, but revisionism to protect new-found sensitivities is pure vandalism. Let us see how people conducted their lives and spoke a hundred years ago without clumsy attempts at censorship. What we now regard as bigotry was normal currency in 1929, even among Priestley’s progressive contemporaries. But only by seeing and understanding this world view in contemporary writing can we appreciate the advances in attitudes that have been made in the past few decades.

Gabby-come-lately: Triumph Gabriele 35 meets the Leica M4

There’s life in the old thing yet

This saga started with the little black and chrome typewriter called The Good Companion, which I carried home a few weeks ago and caused me to disappear into the rabbit hole. And when reading Bill Palmer’s wonderful bringing to life of his old Leica IId, I was reminded of my Good Companion. What must this little machine have seen, from the outbreak of war until the day it ended up on my shelf? Perhaps one day I will try my hand at emulating Bill.

Which brings me back to Priestley. One of his most charming abilities was the way in which he could anthropomorphise objects, a picture, the clouds or, charmingly, a tune. It is not only the beautifully drawn characters in novels such as Angel Pavement or The Good Companions, it is the everyday objects, from the London tram to Miss Matfield’s typewriter and Inigo Jolifant’s piano that take on a mischievous life of their own.

For several days an unusually impudent and delicious little tune had been capering at the back of his mind, and now, after some preliminary flourishes, he set out to capture it. He fumbled about for a few minutes in the key of D major, but then slid into his favourite E flat. The next moment the poor hulk of a piano leaped into life. The tune was his, and he began toying ecstatically with it. Now it ran whispering in the high treble; now it crooned and gurgled in the bass; and then, off it went scampering, with a flash of red heels and a tossing of brown curls. There was no holding it at all. It pirouetted round the room, mocking the desks and blackboards and maps: the air was full of its bright mischief. Rumpty-dee-tidee-dee, Rumpty-dee-tidee.

— The Good Companions

There is also abundant life left in J.B. Priestley’s novels and plays (such as the evergreen An Inspector Calls, first published in 1945 in the Soviet Union — perhaps Orwell wasn’t far from the mark after all). I shall be eternally grateful to my new Imperial Good Companion for reintroducing me to an author whose novels continue to delight even after a century.

A challenge to go back in time

Just in case you are prompted by this essay to rediscover Priestley — or, perhaps, set out on a new journey of discovery — here are a couple of Amazon links (we receive a minute commission if they are used) to the two novels mentioned in this article. I can thoroughly recommend both, especially if you take a nostalgic view of England as it was a century ago. I can promise you an absorbing read and, possibly, entry to a new world of over 30 period “modern” novels.

If this article persuades you to read The Good Companions or Angel Pavement, please write to let us know your reaction… Has Priestley had his day? Is Priestley ready for a new generation?

Read klack goes the keyboard

NOTE ON RELATIVE VALUES: Harold Turgis, a clerk in the offices of Twigg & Dersingham (Angel Pavement) received “six pound notes, one ten shilling note, and two florins” as his fortnight’s wage. This represents £3. 7s. a week (£3.35). His boss, chief clerk George Smeeth, kept a family of four on £375 a year, equivalent to £7.20 a week. Miss Matfield’s “superior” lunch (that is, expensive by 1929 standards) of “a cutlet and peas, apple tart and cream, and a cup of coffee” was 2s 6d (or half a crown comprising 30 old pence). This represents just 12½ new pence, now not enough to cover a sugar lump in her cup of coffee. A filling, but less superior, feast could have been had for 9d (or 4p in our “new” decimalised currency).

Want to contribute an article to Macfilos? It’s easy. Just click the “Write for Us” button. We’ll help with the writing and guide you through the process.

They Hillman Imp factory was in Renfrew built by misguided government subsidy

I remember at the time that is was lauded in the press as a true competitor to the Mini which had been launched (I think) in 1959. As you say, however, it was a misguided venture. It involved components being ferried around the country, back and forth to the Midlands, just to bring industry to Renfrew. It’s a wonder the Mini survived all the disasters of British Motor Corporation in the 1970s.

A fantastic article that took me down a rabbit hole to the point I happily forgot what I was supposed to be doing this morning after I clicked on MacFilos. Thanks for including the link to the film…Now that I’m holed up in Japan, where I sometimes participate in all the ritual of the Japanese tea ceremony, it was good to be reminded of that quaint British custom of sipping tea from a saucer which I had totally forgotten about but remember doing as a young lad growing up in Lincolnshire. I can’t help but imagine that seeing these magnificent old typewriters will, in a similar way, bring back fond memories from many of your readers.What a great read this was. I dip my biscuit to you. 🙂

Stephen, many thanks for your appreciation of the story, and I’m glad it took you down a rabbit hole of your own. That film is a corker, as they used to say at the time, and made at the beginning of the “talkie” era. The book itself was written at the end of the silent-film era, and the film of The Good Companions must have seemed very modern when it was first shown. It never does us any harm to look back in time and, in this case, understand how our great and great-great-grandparents were living. Thanks again.

Mike

Being your age, Mike, but a Yank, I will say that typewriters were a constant companion until perhaps 35 years ago. I have had Olympus machines, and still have a Smith Corona standard, gathering dust. But I don’t know the British brands at all. At one time though I hankered after a Wanderer Continental, like the portable that Dr. Paul Wolff used.

And about monetary inflation. I love to use a rule of thumb here: simply divide all current prices by 10 to arrive at their “real” worth (i.e. the price in my early life). Hence $120.00 of groceries, was like $12.00 worth when I was a child. A $45,000 car is like a $4,500 car from my college years.

It all works until there is more inflation.

Ed

Thanks, Ed.

You must be a mere youff, Ed. My first NEW car, a Hillman Imp, cost £512 (including £10 for a heater). As for typewriter brands, it’s confusing. Many American brands were also manufactured in Britain, and they changed hands frequently. Imperial was founded in Leicester in 1911 by a Spaniard. I’m certainly no expert, but John Tanner, mentioned in the article, knows a lot about the old industry.

I don’t know what it is about typewriters, but they just fascinate me and have played such an important part in my life and work.

My first real car was a Volvo 122S, which cost about £900 equivalent new. My parents paid for it! I drove it into the ground, rust and all, then my ex-girlfriend took it. Before that I had an Opel Rekord which had belonged to my grandmother — I have no idea what that might have cost. This all in the late 50s to mid 60s.

I cannot really imagine going back to typewriters now, because I make so many keyboard errors. Back to cars: if my driving was like my typing now in my 80s, I wouldn’t be allowed on the road.

I seem to remember that the Hillman Imp – like the Volkswagen Beetle – had a spare engine in the back.

I DO remember ..working as an AA (Automobile Association) breakdown mechanic.. going out to a woman who’d put frying oil in the brake fluid reservoir of her Hillman Imp, as she’d run out of proper brake fluid. Couldn’t be driven.

The Hillman Imp was, of course, the ‘car of the future’ in the film Alphaville (..among many others).

My, my, you have had an interesting career, David. AA breakdown mechanic now. That’s a new one on me. But you are right about the Hillman Imp. With its state-of-the-art engine at the back, just like a Porsche for peanuts, it was a thoroughly modern mini. It emanated, I think, from a factory in Scotland. Sadly, it was unreliable, among its other failings, and I remember going through at least two clutches under warranty. But that could have been my driving, of course, so let’s not be too hard on the Imp. I sold it in favour of a two-pane-rear-window Volkswagen Golf from 1950 which still had Czech number plates attached and, of course, was left-hand drive. I drove that old banger to and from Berlin on three occasions, and it never missed a beat. Frankly, I wouldn’t have trusted the new Imp to Boulogne, never mind Berlin.

Fascinating to combine an old typewriter, old camera, old pen and old desk into a reviw of Priestley. Great read and thanks. I think I’m going to try reading those two novels thanks to your enthusiasm.

Thanks, Andy. As I said, it was a real bunny hole. It was only when I came to take the pictures that I thought about all the possible connections. It all came together beautifully.

Mike

What a wonderful story, Mike. I also love typewriters and have two, an old Imperial Standard and a a Royal portable here at my home in Southampton. I remember when I started work as a bank clerk in 1958 there was only one mechanical aid in the whole branch, apart from the single telephone sitting in a mahogany kiosk at the back of the office. We didn’t even have a mechanical adding machine and everything had to be done by mental arithmetic. But the sold nod to the modern era was a rather old Bar-Lock typewriters which handled all the manager’s correspondence. It was also used to copy the handwritten ledgers onto pre-printed statement forms. I remember having to copy a ledger while an impatient customer stood at the counter. Those were the days when the customer was king, not the staff as is the case these days.

You are right, George. Back in the early sixties, office life had not changed materially since the late Victorian era. And it really wasn’t until the 1980s, when PCs became common in smaller offices, that things started to move. This brings me to another subject, prices. In the period up to as late as 1980, labour was relatively cheap, but manufactured goods relatively expensive. That Imperial typewriter at £14 in 1929 was hideously expensive by our standards. The same went for cars, motorcycles, almost any manufactured product before the world war. But you could hire a cook for £50 a year plus board.