The First World War had a devastating impact on Britain, as it did on so many other countries. A generation of men died; and with them died the aspirations of a generation of sweethearts and wives, many of whom chose to spend the remainder of their lives unmarried. For the fifty years after the war, this upheaval was palpable.

Our First World War Centenary Woods were created to give thanks to those who gave so much. Over four years we planted hundreds of thousands of trees to represent the millions of lives lost and affected by the conflict. Four flagship woods have been created in each of the UK’s countries, providing a living legacy to all those affected by the conflict. They stand now as places of peace and beauty to remember and reflect.

So begins the description of the First World War Centenary Woods on the website of the Woodland Trust. The centenary wood in England is at Langley Vale behind the downs at Epsom, home to the famous Derby horse race. Take a look at the Langley Vale Wood website here.

This article, the second in the series, describes the large oak sculpture entitled Witness which sits immediately behind the Regiment of Trees. I have built this article around my correspondence with the sculptor, information from the internet (references noted as much as possible) and my own thoughts and photographs.

Witness

In March 2021, I decided to walk around the wood to look for interesting compositions to photograph with the intention of adding to my pictures of The Regiment of Trees. I was surprised to see two men, John Merrill and Ethan Stote, erecting a wooden structure. The sculptor, John Merrill, kindly told me about it. He also bore with me as I hung around taking photographs that afternoon and the next. I had been fortunate to visit on the one weekend they were erecting it on site.

The following description was taken from the Woodland Trust website.

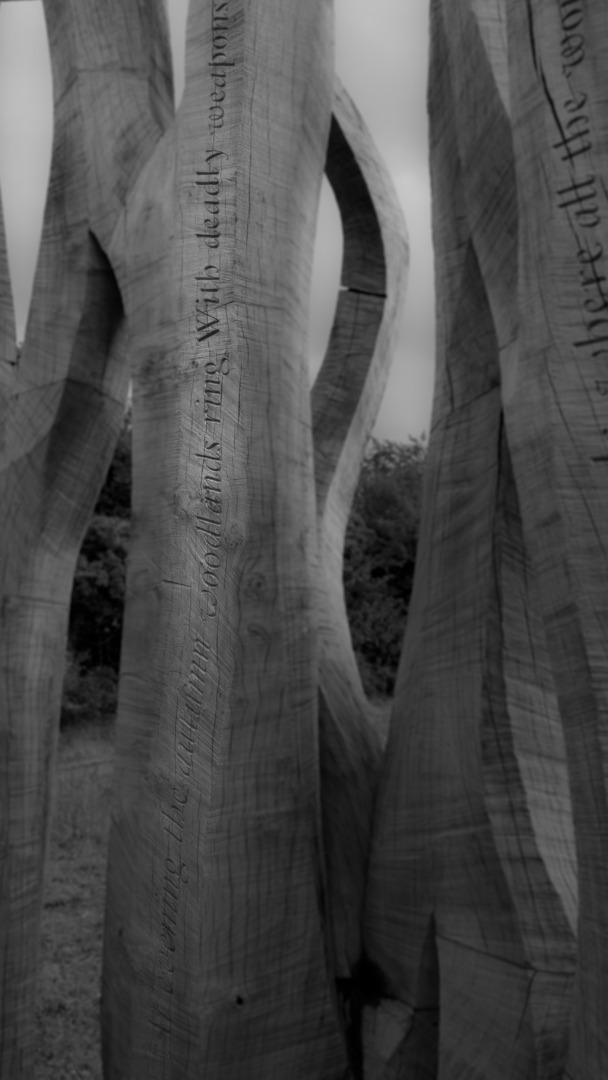

Measuring approximately six metres tall and four metres in diameter, and carved with words taken from seven poets of the period, this First World War memorial feature creates a space for contemplation. Constructed from around 35 pieces of oak, it weighs about the same as a fully-laden London double decker bus. Sculptor John Merrill describes how it was ‘originally inspired by the paintings of Paul Nash (the official war artist), the desolate landscapes and desecrated trees and his passion for the natural environment’.

John elaborates on the theme in a video presentation which you can view here.

The transcript of the video, also included on the website, is as follows in his own words:

“The site where the sculpture is going is a new memorial woodland, which is presently being planted by the Woodland Trust on the Epsom Downs, and the thing that struck me about the site was how little woodland is there at present.

“So, my initial sort of response was to create a woodland and there seems to be this really strong connection at that point between the memorial woodland being a sort of 14-18 war memorial to commemorate the centenary of the First World War and the paintings of Paul Nash, the official war artist of both the First and Second World Wars.

“So, there was this really strong relationship between the war, the landscape and these paintings of woodlands by Paul Nash and the trees which you know he painted obviously were part of these devastating landscapes.

“It’s essentially an enclosure of trees that’ll be 5 to 6 metres tall and 4 metres in diameter. It consists of essentially a sort of nine uprights that interconnect at various stages as it goes up to give it a sort of structural integrity. The big pieces will form the lower section of the sculpture and then where they fork and branch, we’ll use those forks and those branches to create some connection points to join the piece together as it goes up.

“There’s probably about 40-odd tonnes in the yard at the minute. We think that in a raw state there’ll be about 36 tonnes goes into the model and once that’s shaped back down, we’re looking at an estimated weight of around 20 to 24 tonnes completed. So, it just gives you some idea of the physical logistics of managing this amount of material.

“Like all pieces of sculpture, hopefully, you think it starts to chew in thoughts as to what is it, why is it here, what’s it for and all those reasons and will hopefully instil a thought or a memory of what has gone on and give people a space to sit and contemplate and think about you know, the atrocity of war.”

I was particularly interested in the way the sculpture had been designed as a structure and noted the stainless steel pins to join the uprights together. I saw the timbers being lifted into position, the resin as it was poured into the sockets to fix the pins and the final alignment of the oak’s edges. Over that weekend, I tried to capture the process of installing the work.

On subsequent visits, when the sculpture was a worksite with no public access and since it opened at the beginning of September 2021, I attempted to represent the completed work with its beautifully carved poetry…

An essential element of the sculpture are the excerpts of First World War poetry carved into the oak; the Woodland Trust website tells me the poems are:

- Futility by Wilfred Owen (1893–1918)

- Matthew Copse by John William Streets (1883-1916)

- Lights Out by Edward Thomas (1878–1917)

- Afterwards by Margaret Postgate Cole (1893–1980)

- May, 1915 by Charlotte Mew (1869-1928)

- The Gift of India by Sarojini Naidu (1879-1949)

- Grodek by Georg Trakl (1887-1914).

The poets’ names are carved into benches placed within the sculpture.

Wanting to delve further, I had the following e-mail exchange with the sculptor John Merrill who kindly answered my questions as below. I am reproducing his words, with his permission, for clarity.

Why did you choose those particular poems? Is it because they all contain references to wood, forests, seeds etc?

JM: The poems are all by WW1 poets which were relevant as the piece is a WW1 centenary memorial which, yes, I selected because of their references to woods trees and nature. The sculpture itself was inspired by war artist Paul Nash painting “Wood on the Downs”

Why did you select the words within the poems? For the same reason?

JM: Yes I looked for references within the poems relating to the decimation of the landscape and specifically woodlands and trees. One of the trees used in the piece is from the childhood garden of the WW1 poet Wilfred Owen in Oswestry. I came across the tree by chance and it was being cut down due to redevelopment and was probably heading to be cut up for firewood.

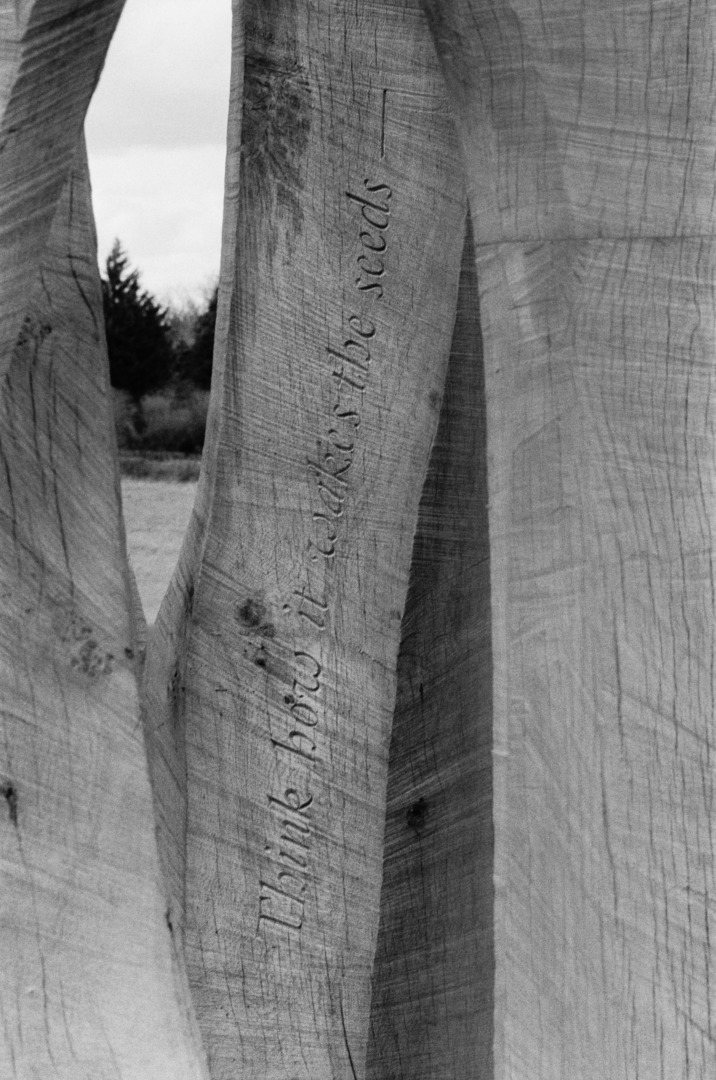

His tree has his words on it, from the poem “Futility” “think how it wakes the seeds”.

I wanted the words to disappear upwards towards the sky and if people are interested in reading the entire poems they will hopefully be able to find them via the Woodland trust website. The intention is that visitors to the piece stand or sit inside, read the words if they choose and contemplate them, the natural environment, the atrocities of war.

Which source did you use for the words?

JM: I read lots of poems online before selecting some, I wanted to get a diverse selection of poets from around the world and by both men and women. Due to copyright we weren’t able to use all of the poems we wanted to, I particularly wanted to include Robert Lee Frost’s “A Road Not Taken”.

Did you carve the words, and if not who did?

JM: We carved the words ourselves with chisels, mainly from a scaffolding. There are approximately 27 metres of text in total.

I have included below a few words about the poets and verses from which the carved fragments – shown in bold type – were taken. To see the beautifully carved words more clearly, the photographs must be expanded on the reader’s computer, phone or tablet. I have sought and obtained where possible permission from the copyright holders to reproduce the text here.

I have referred to the carved words as fragments. Their embedding in the wood, representing the creative beauty of the human spirit, contrasts with the destructive fragments of exploding shells that reduced the once beautiful trees to shattered stumps.

Futility by Wilfred Owen.

Owen enlisted in the Artists Rifles on 21 October 1915 and on 4 June 1916 was commissioned as a second lieutenant (on probation) in the Manchester Regiment.

Caught in the blast of a trench mortar shell, he spent several days unconscious on an embankment lying amongst the remains of one of his fellow officers. Soon afterwards, he was diagnosed as suffering from neurasthenia or shell shock and sent to Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh for treatment. He returned in July 1918 to active service in France and at the very end of August 1918, he returned to the front line. He was killed in action on 4 November 1918, exactly one week (almost to the hour) before the signing of the Armistice which ended the war, and was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant the day after his death.

He is buried at Ors Communal Cemetery in northern France.

On 11 November 1985, he was one of the 16 Great War poets commemorated on a slate stone unveiled in Westminster Abbey’s Poets’ Corner. The inscription on the stone is taken from Owen’s “Preface” to his poems: “My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity.” (Reference Wikipedia).

I found John Merrill’s comment about the tree on which the words are carved, mentioned above, particularly moving.

From Futility:

Move him into the sun— Gently its touch awoke him once, At home, whispering of fields unsown. Always it woke him, even in France, Until this morning and this snow. If anything might rouse him now The kind old sun will know. Think how it wakes the seeds— Woke once the clays of a cold star. Are limbs, so dear-achieved, are sides Full-nerved, still warm, too hard to stir? Was it for this the clay grew tall? —O what made fatuous sunbeams toil To break earth's sleep at all?

Matthew Copse by John William Streets.

John William Streets, better known as Will Streets, began work as a miner at the age of fourteen, continuing to educate himself in his spare time. Joining the Sheffield City Battalion (Sheffield Pals) in August 1914, in late 1915 and early 1916 he served in Egypt. The battalion was subsequently transferred to the Western Front.

Streets, by this time a sergeant, was wounded on the first day of the Battle of the Somme, and subsequently went missing. His body was eventually recovered exactly ten months later, on 1 May 1917, and he is buried at Euston Road Cemetery, Colincamps, France.

His poems were posthumously published in the same year under the title The Undying Splendour. (Reference Wikipedia).

From Matthew Copse:

Now 'mid thy splinter'd trees the great shells crash, The subterranean mines thy deeps divide; And men from Death and Terror there do hide – Hide in thy caves from shrapnel's deadly splash.

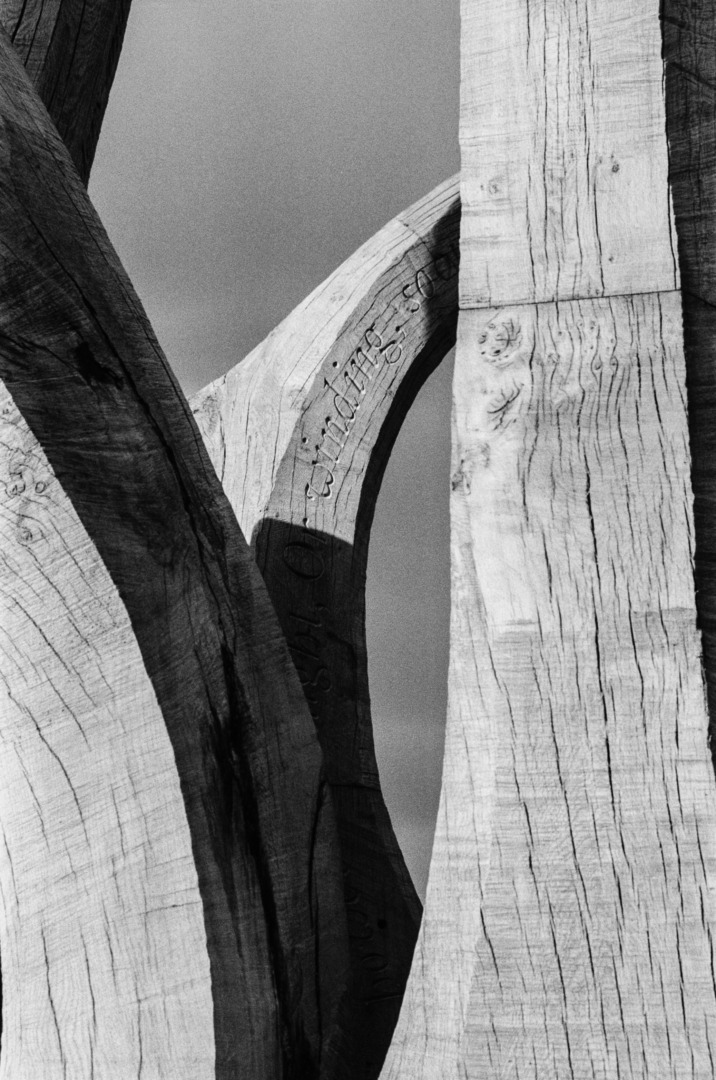

Lights Out by Edward Thomas.

Thomas was already a seasoned writer by the outbreak of war, having published widely as a literary critic and biographer as well as writing about the countryside. He enlisted in the Artists Rifles in July 1915, despite being a mature married man who could have avoided enlisting.

Promoted to corporal in November 1916, he was commissioned into the Royal Garrison Artillery as a second lieutenant. He was killed in action soon after he arrived in France at Arras on Easter Monday, 9 April 1917. He is buried in the Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery at Agny in France (Row C, Grave 43). (Reference Wikipedia).

From Lights Out:

I have come to the borders of sleep, The unfathomable deep Forest where all must lose Their way, however straight, Or winding, soon or late; They cannot choose.

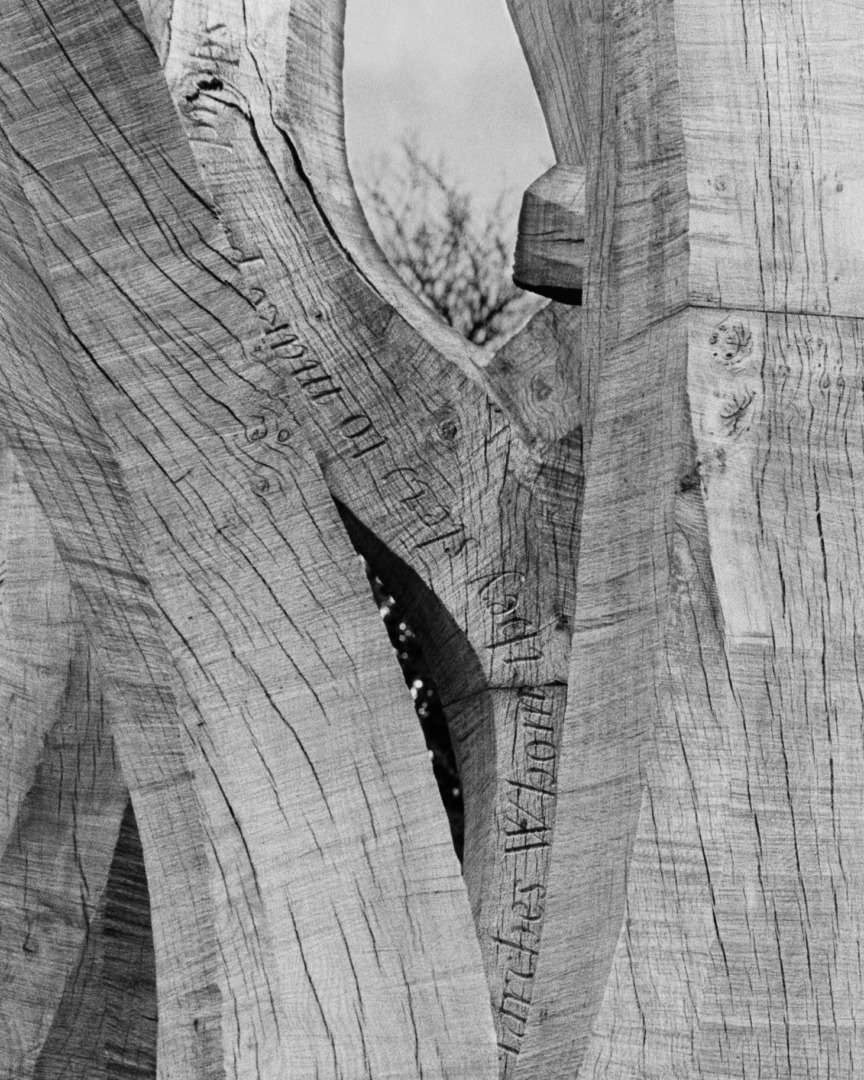

Afterwards by Margaret Postgate Cole

Dame Margaret Isabel Cole DBE (née Postgate; 6 May 1893 – 7 May 1980) was an English socialist politician, writer and poet. (Reference Wikipedia).

From Afterwards:

And peace came. And lying in Sheer I look round at the corpses of the larches Whom they slew to make pit-props For mining the coal for the great armies.

May, 1915 by Charlotte Mew.

Charlotte Mary Mew (15 November 1869 – 24 March 1928) was an English poet. (Reference Wikipedia).

From May, 1915:

Let us remember Spring will come again To the scorched, blackened woods, where the wounded trees Wait, with their old wise patience for the heavenly rain, Sure of the sky: sure of the sea to send its healing breeze, Sure of the sun. And even as to these Surely the Spring, when God shall please, Will come again like a divine surprise To those who sit to-day with their great Dead, hands in their hands, eyes in their eyes At one with Love, at one with Grief: blind to the scattered things and changing skies.

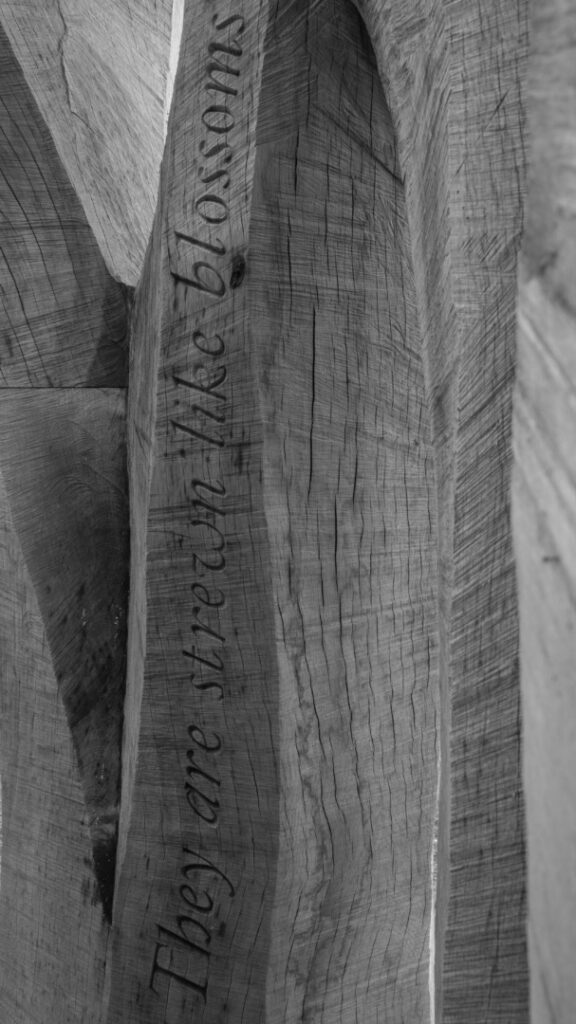

The Gift of India by Sarojini Naidu.

Sarojini Naidu (née Chattopadhyay; 13 February 1879 – 2 March 1949) was an Indian political activist and poet. Naidu’s work as a poet earned her the sobriquet ‘the Nightingale of India’, or ‘Bharat Kokila’ by Mahatma Gandhi because of the colour, imagery and lyrical quality of her poetry. (Reference Wikipedia).

From The Gift of India:

Is there aught you need that my hands withhold, Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, And yielded the sons of my stricken womb To the drum-beats of duty, the sabres of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, Scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, They lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, They are strewn like blossoms mown down by chance On the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France.

Grodek by Georg Trakl.

Georg Trakl (3 February 1887 – 3 November 1914) was an Austrian poet and the brother of the pianist Grete Trakl. He is considered one of the most important Austrian Expressionists perhaps best known for his poem Grodek. (Reference Wikipedia).

The poem was originally written in, and the carved words are translated from, German.

From Grodek:

At evening the autumn woodlands ring With deadly weapons. Over the golden plains And lakes of blue, the sun More darkly rolls.

Final thoughts.

Within Witness the fragments of the poems and the twisted trees stand together, the exquisitely carved lettering juxtaposed with the roughly cut wood. As John Merrill intended, the words disappear upwards towards the sky as though carried by the twisted trees. I look forward to being able to sit and reflect within it, surrounded by words and wood, as only then will I experience it as he intended.

Epilogue

At the beginning of September 2021, John Merrill the sculptor e-mailed to say that the fencing had been removed and the structure is now open to the public. I hope you will be able to visit it, sit awhile, and reflect.

Footnote

Most of the photos were taken with a Leica X Vario. Photos numbers 12, 20 and 22 were taken on an Olympus IS3000 using Ilford HP5 Plus (ISO400) film. Numbers 28 and 29 were taken on an iPhone 5S.

Read the first article in this series: The Regiment of Trees

Read more from Kevin Armstrong

Want to contribute an article to Macfilos? It’s easy. Just click the “Write for Us” button. We’ll help with the writing and guide you through the process.

A lovely piece with great photos, Kevin. I’m always in two minds about war memorials. On the one hand, war is not really a subject that should be memorialised itself, but the people who got caught up in or suffered in wars should always be remembered. Somehow the use of wood, which is a material found in nature, and the words of poets makes this memorial somehow more natural and human than others that I have seen. All that being said, I did my own little tribute here on Macfilos some years ago when I photographed the main war memorial here in Dublin with a Vest Pocket Kodak (‘The Soldier’s Kodak’) from 1915. I’m still trying to figure out what I was doing, but I always regard a camera as ‘another eye’ and a photo as ‘another memory’.

You may recall that my friend Mark Scott from Belfast had a story here on Macfilos about George Hackney a soldier who took photos in the battlefield in World War I and that Mark had written about him in a book called ‘ The Man Who Shot the Great War’. Mark has another book out now called ‘Among the Kings’ which deals with, among other things, the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior in Westminster Abbey. The book deals with how the remains that are in that tomb were selected and what happened to the remains which were not selected. On 12th November Mark will be giving a talk at the National Army Museum in London about the contents of this book, which I think that a lot of readers here will find very interesting. This can be viewed online and details are available from the National Army Museum website under the ‘What’s On ‘ section. I will send Mike the connecting link.

William

Thanks William. I agree with your sentiments; one of the good things about Witness is that is a place to sit and reflect. I’ll look out for the new book you mentioned.

Thank you for chronicling the building of this sculpture. To me, the organic nature of oak makes it more relatable to humanity, compared to steel or stone or concrete. And the etching of the words of the poets is a wonderful touch. Imaginative and very meaningful.

Thanks Wayne, I agree. I am not aware of the original brief from the Woodland Trust about the structure but those involved in its construction, in particular John Merrill and Ethan Stote, are to be congratulated.

Thank you Kevin – a wonderful article, weaving together photography and poetry with the story of the sculptor’s vision. I really appreciate all the work you put into compiling the material. All the best, Keith

Thanks Keith, Witness struck a chord with me as my grandfathers fought in WWI and their experiences and the consequences remain with me albeit with diminishing affect as the years pass.

Poignant, Prescient Words to the Futility of War.

Thank you.

Thanks, I agree. War is a sad fact of humanity’s existence.

really interesting article and great accompanied images. Looks well worth a visit

Thanks Richard, I think the Witness structure is the most moving of all the installations in the wood.

Fascinating article and series of photos.

Thanks for sharing

Jean

Thanks Jean, glad you enjoyed it.

Fabulous article and pictures Kevin thank you for sharing it with us. Don

Thanks Don, much appreciated.

Thanks so much for this Kevin: MY eldest son, who died too young, was buried in a very moving ceremony in a woodland resting place near Newark, Notts. This promises to grow into a beautiful place of reflection and memory. I will certainly visit when time and the pandemic permit.

Thanks for your comment Tony. I tried to capture and illustrate the intentions of the sculptor John Merrill and the Woodland Trust who commissioned him.

Thank you, Kevin, for your words and photographs. A very appropriate approach and you have inspired me to visit the site as soon as possible.

Thanks Frank and I think you’ll be impressed by the Centenary Wood installations.

Thank you very much for sharing, Kevin.

Thanks Richard.

Forget the sights of London orThe Royals! Just go here, what a magnificent tribute! I remember reading some where about an officer leading his men out of trenches, to cross the battlefield, and he dribbled a soccer ball and said PLAY UP, PLAY UP AND PLAY THE GAME! I don’t know if that is a true story, but it epitomizes WW1.

Thanks John, much appreciated. The story may be true as the words came from the poem Vitai Lampada by Sir Henry Newbolt which, I read, was popular during the early part of WW1.

Excellent piece, Kevin. I’ve forwarded the link to a dear friend who is a military historian and I’m sure he will find it interesting. I like that you chose to show the sculptures in black and white.

Thank you Farhiz, I’m glad you enjoyed it and hope your friend does as well. He might be interested also in the previous article on The Regiment of Trees.