“The intelligence which has emanated from you before and during this campaign has been of priceless value to me. It has simplified my task as commander enormously. It has saved thousands of British and American lives and, in no small way, contributed to the speed with which the enemy was routed and eventually forced to surrender.”

General Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, wrote these lines on 12 July 1945 in a letter to Major General Sir Stewart Menzies, the Chief of the British Secret Service at the end of the Second World War.

Bletchley Park and the Ultra organisation were part of his Secret Service. The intelligence which was given to General Eisenhower was called Ultra, and the word itself was secret.

Ultra was a category of secrecy “beyond most secret”, used to describe intelligence derived from intercepting and breaking the high-level encrypted wireless and teleprinter traffic from the German Enigma and Lorenz cypher machines.

The codebreakers at Bletchley named the traffic sent via the Lorenz machine as “Tunny”, a fish species. There was a logical reason, but that’s another story. The Italians used a cypher machine called Hagelin to a lesser extent, which also fell under the Ultra umbrella.

Only the select few on the approved Ultra list were allowed to receive this intelligence via special liaison officers. My father was one such SLO, and I told his story in the article, The Ultra Secret: Sensationalist Nonsense.

Enigma and Lorenz were two very different cypher systems and had very little in common. Enigma, with its three wheels, created messages using the twenty-six-letter alphabet. However, the Lorenz SZ40/42 was a much more sophisticated machine with twelve wheels, 501 pins and used a teleprinter code.

The Enigma machines were produced in many hundreds and were deployed throughout the German armed forces. However, Lorenz was used only by Hitler and his top generals for strategic communications, and only around fifty were ever made.

Over in America, the intelligence cryptographers realised the Japanese Foreign Office used a cypher machine to encrypt its diplomatic messages. The device was called “Purple” by the Americans, and they built a machine capable of breaking this code. So with that sketchy prior knowledge from these diplomatic messages, could the attack on Pearl Harbour have been prevented in 1941? Unfortunately, despite numerous commissions and investigations over the years, there can still be no real answer to that question.

In May of 1943, as a result of an agreement between the US War Department and the British Government Code and Cipher School at Bletchley Park, the Americans established a branch of their Military Intelligence Service in London, supplementing the fifty personnel working at Bletchley Park.

Up until that date, the intelligence from the American Purple machine was called Magic. But after that, all intelligence gathered from the various cypher machines was then called Ultra by all the Allies.

So what was the process for producing Ultra intelligence? The Government Code and Cipher School at Bletchley Park received high-level enemy wireless traffic from intercept stations (known as Y stations) dotted around the UK and also abroad from such places as Malta.

In the case of Enigma, traffic was in Morse code; or in the case of Lorenz, it was in the form of wireless teleprinter language. At Bletchley, the traffic was decoded by hand but, where possible, with help from new inventions: Bombes in the case of Enigma; Heath Robinson, Colossus (Marks One and Two) and the Tunny Decoder machine in the case of Lorenz.

Rebuilt Turing Bombe – Photograph Chris Rodgers Inside rebuilt Turing Bombe – Photograph Chris Rodgers

Wartime image of the Colossus computer Rebuilt Colossus computer at the National Museum of Computing – Photograph Mike Evans

The decoded material was then translated, corrected, analysed for intelligence, comments attached; before the messages were sent to the relevant recipient via the special liaison units.

Since 1974 material has gradually been made available about Enigma and Ultra, not only from public records but also from personal testimony. However, a significant part of the story, the Lorenz cypher machine and its codebreaking, remained classified until 2002. By that time, most of the veterans were no longer alive. However, Captain Jerry Roberts, who died in 2014, aged 93, was able to give details of the Lorenz machine and the Tunny code during the last years of his life. Jerry Roberts was a skilled linguist, fluent in German and a formidable codebreaker.

Enigma and Bletchley Park are regarded by many as synonymous, and this has all but eclipsed the Lorenz story.

Also, by the very nature of secrecy, work was compartmentalised. So, for example, intelligence analysts in Hut 3 would have had little idea of what was going on in Hut 6, where the codebreakers worked. So one person could not give a comprehensive account of what went on at Bletchley in all the different sections.

Another example was the “Testery” (named after Ralph Tester), which for twelve months from mid-1942 undertook all of the Tunny code-breaking stages by hand, did not engage personally to any great extent with the “Newmanry” (named after Max Newman) after it was set up in mid-1943.

Instead, the Newmanry concentrated on providing machine assistance for the codebreaking. Its first task was to commission the Heath Robinson machine, which electro-mechanically worked out some of the wheel patterns of the Lorenz machine for the particular message to be decoded. In 1944 Tommy Flowers, a Post Office engineer, created history by developing the Colossus computer, which used thermionic valves (vacuum tubes). Colossus, Marks One and Two, increased the speed, reliability and capacity of what the Heath Robinson machine attempted to do.

The Testery, in which Jerry Roberts was a founder member, consisted of linguists with a knack for code-breaking by hand, and the Newmanry consisted of mathematicians and engineers. They were not naturally of the same tribe and did not understand each other’s work; only the result of their work.

I believe there is now enough published material to give a balanced account of the Ultra story, and I do not think there are any more secrets or personal testimonies yet to be unveiled. However, Captain Jerry Roberts’ Lorenz book was published posthumously as recently as 2017 and revealed just what went on in the Testery.

Much of the information already published is just plain wrong when it describes the breaking of Tunny. The misinformation is that it took weeks to break the Tunny code by hand. Jerry Roberts says he was breaking several messages by hand alone during an eight-hour shift.

The problem was that the hand breaking methods couldn’t keep pace. The German operators tightened up their security and the number of messages kept increasing. Skilled codebreakers were a scarce commodity; that is why the introduction of the Colossus computers was so vital. During the war 64,000 Tunny messages were successfully decoded; the majority were with the assistance of Colossus.

The combination of computer and brain power meant that only ten per cent of all encrypted Tunny messages received by Bletchley Park were unable to be broken.

Several Tunny messages Jerry Roberts personally broke by hand in early April 1943 gave details of the planned German offensive in the Kursk area on the Russian front, which began on 5 July 1943. This information was passed to Stalin and, together with local intelligence, enabled the Russians to prepare for the forthcoming battle. By winning this major strategic battle, albeit with massive casualties, the Russians turned the tide on the Eastern Front.

How Stalin received the information is another story. It involved the Soviet spy at Bletchley, John Cairncross—the fifth man of the Cambridge five spy ring—sending Ultra decrypts to Russia via his handlers. It also involved a secret service ruse of a supposed German spy sending details to the British.

This information (its real source at the time was thought to be disguised) was then passed on through the British Military Mission in Moscow. How much Stalin knew about the actual code-breaking at Bletchley remains open to debate. What he did know, though, three months in advance, were the intentions of the Germans and a breakdown of all their forces that were to be used for their offensive.

Bletchley Park and Ultra have now been brought to wider public attention with films such as the 2015 “Imitation Game”, but in many aspects, the film is inaccurate and gives a false impression of what went on at Bletchley. It deals solely with Enigma, and even then, the plot plays lip service to reality.

I would like now to deal with the Enigma and Lorenz cypher machines themselves: how they worked, how they were used and how the codes were broken.

Enigma

Enigma, the three-wheel cypher machine, was:

- Declassified in the 1970s

- Used from 1923 onwards, for air, land and sea traffic

- Well known through print, television and film

There are some excellent websites that explain the Enigma story and how the Enigma machine code was broken.

It is in this Enigma story that Alan Turing and Gordon Welchman are the real heroes. It is not, in my opinion, an exaggeration to say that by breaking the naval Enigma code, Alan Turing helped Great Britain survive during those dark days of 1941.

By knowing the U Boats’ positions, convoys could be rerouted so vital supplies of food and materials could still reach Britain. However, there was an intelligence blackout in the summer of 1942 when the Enigma key settings changed and that resulted in widespread shipping losses. Fortunately, Alan Turing broke the revised code in December 1942.

John Harper has published some web pages (bombe.org) which give a wealth of detail about the Enigma story so you can dip in and out as you wish.

The Enigma Machine – bombe.org.uk

Enter Turing and Welchman – bombe.org.uk

The two Numberphile videos (links below) are, in my view, a revelation. They explain in very simple terms the workings of the Enigma machine and the flaws built into it, and also how these flaws enabled the codes to be broken. The major drawback was that no letter could be encrypted back to itself.

The casual reader may like to forego the two videos by Dr James Grime. However, they are not technical, and each has had over four million views.

The first video, twelve minutes, explains how the Enigma machine worked:

The second video, eleven minutes, explains how the code was broken:

Lorenz

Lorenz, the twelve-wheel cypher machine was:

- Declassified only in 2002

- Used from 1940 onwards by the German Army

- Used by Hitler, his high command and top generals

- More advanced, complex, faster and more secure than Enigma

Watch these two short BBC video clips, each of about two minutes.

In the spring of 1942, Bill Tutte worked out the logical structure of the Lorenz machine without ever having seen it. This feat has been described as one of the most outstanding intellectual achievements of the war.

It took him nearly three months of concentrated effort with a pencil and paper, sitting quietly in the research section at Bletchley. Once they knew the logical structure of the Lorenz machine, the codebreakers in the Testery switched their efforts from another code to work solely on the Lorenz code (Tunny).

When they broke the Tunny code and the wheel settings discovered, they put the settings into the Tunny Decoder machine. They simply typed in the coded text, and the plain text came out in German ready for translation.

The Tunny Decoder machine was the first of several to be commissioned. Heath Robinson, Colossus Mark One and Colossus Mark Two then followed. Without them, vital intelligence would not have been available to the Allies.

The casual reader may just like to be content to know that the people who designed and built the machines were geniuses and leave it at that. The heroes of the Lorenz story are Bill Tutte, Tommy Flowers and Alan Turing.

Bill Tutte’s home town of Newmarket in Suffolk, where he was born, built a memorial to him in 2014. The website also has details about Bill Tutte’s life and the codebreaking of Lorenz.

In 2020, Martin Gillow, a computer programmer, produced a website that answers in a more technical way nearly all the questions relating to the Lorenz cypher machine and how its code was broken.

The page explaining the Newmanary machines is shown below, but as I mentioned earlier, he is wrong to say the hand breaking of messages took weeks because one message could be done in a matter of hours. There were just too many messages to be decoded by hand by skilled linguists.

Virtual Colossus – The coming of the machines

If you would like to go into more detail, visit this link and scroll down the page to see a list of all its contents and select what you would like to read.

Included is also a twelve-minute video by Dr James Grime explaining how the code was broken by hand and how the machines dovetailed into that process:

From the website, you may like to try the “Virtual 3D or 2D Colossus” and for any self-confessed geeks out there, try some simulations.

The real story of Bletchley Park and Ultra is one of teamwork on a massive scale, in which good management and effective procurement were just as crucial as individual scientific genius. Turing, Welchman, Tutte and Flowers did not win the war by themselves; however, without them, the outcome of the Second World War in 1945 may have been very different.

Sir Harry Hinsley, who died in 1998, was employed in Naval Intelligence at Bletchley during the war and later became an eminent historian at the University of Cambridge. By using a technique called counterfactual history he calculated that Ultra shortened the war in Europe by not less than two years and probably by four years. He readily admitted that such a strict calculation could not take into account something like the development of the atomic bomb by the Americans in the second half of 1945.

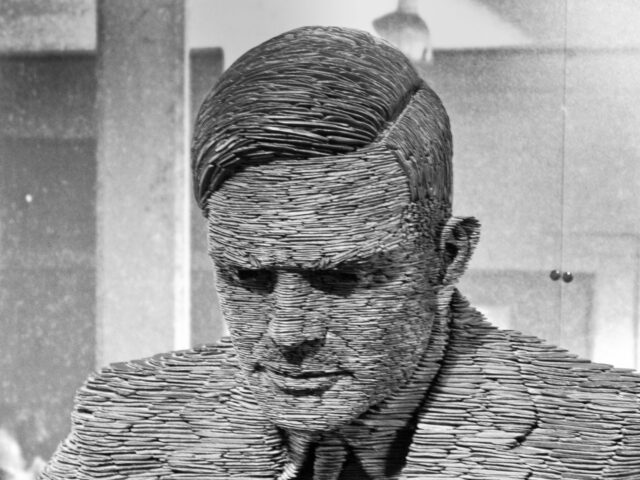

Please Listen – Photograph Mike Evans Slate sculpture of Alan Turing – Photograph Mike Evans

Ultra, however, did not give unambiguous intelligence on nearby German troop dispositions before the battle of Arnhem (August 1944) and on German preparations for the Ardennes offensive (December 1944), with both actions leading to many Allied casualties.

But an indisputable fact remains: Ultra was overall of “priceless value” to the Allies.

So to sum up, thanks to the hero codebreakers and all staff at Bletchley Park, Ultra:

- Helped to win the Battle of the Atlantic against the U boats

- Saved Egypt from being overrun in the Western Desert, thereby protecting the Suez Canal and the Persian oil fields.

- Provided vital intelligence before the decisive Battle of Kursk on the Russian Front

- Provided vital intelligence for the planning of D Day; without it, it is doubtful the D Day landings would have succeeded in 1944

- Saved the Anzio beachhead in Italy from annihilation

- Gave strategic information on the Italian campaign, thereby tying down one million German troops in Northern Italy

- Provided various tactical intelligence in the Battle of Normandy and the South of France landings, thereby reducing casualties

One question remains, however, Why was the Lorenz cypher machine only declassified in 2002? Could it be that Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) at Cheltenham were still breaking Lorenz type machine cyphers after the war and that valuable intelligence was still being produced?

A theory is that the Russians never realised Lorenz had been broken (Enigma – yes), and after the war, they used captured machines for communications in the Warsaw Pact countries early in the Cold War.

However, in 1956 the Russians introduced their own cypher machine called Fialka for use in the Warsaw Pact. It used punched tape and had ten rotors. It was declassified only in 2005. Was this code broken by GCHQ? There is no evidence that it was.

As of yet, there is no public explanation of why the efforts of Bill Tutte and Tommy Flowers were kept secret for so long and therefore became Bletchley Park’s lost heroes.

Secrecy was not always maintained as Russian spies in the 1960s and 1970s (Geoffrey Prime at GCHQ England, John Walker and Christopher Boyce in America) damaged the Allies’ code-breaking efforts for several years.

Even now, in 2021, internet and mobile phone surveillance can dominate the headlines in the age of the internet and smartphones. The Edward Snowden affair of 2013 still has repercussions. He finally defected to Russia after stealing a vast quantity of documents from his employer, the National Security Agency in America and disclosed surveillance methods employed by America and its Allies in intelligence.

It would be interesting to surmise what is happening nowadays throughout the world in codebreaking, surveillance and covert malware.

In the interests of our own UK national security, I wonder what tasks the many thousands of people who are now employed at GCHQ Cheltenham are engaged in?

Such knowledge would be secret or to use an old code word “Ultra” secret.

Read more from Chris Rodgers

Want to contribute an article to Macfilos? It’s easy. Just click the “Write for Us” button. We’ll help with the writing and guide you through the process.

Thanks for a fantastic overview of Ultra and especially the info on Tunny. Nice to see others letting people know about this amazing side of the Bletchley Park story and the incredible people which are so eclipsed by Enigma!

Thanks also for the links and mention. I wrote up the docs for the page mentioned a long while ago after my first Virtual Colossus so can’t recall exactly where the timescale of weeks came from exactly. Jerry Roberts book states a general breaking time of 3 hrs to a day once they were used to working on Tunny so the weeks time could just be from an estimate on how long the initial breaking calculations as Robinson/Colossus did to be done by hand.

If you haven’t seen it yet, check out my new 3d simulation of Enigma which was just released a few days ago : enigma.virtualcolossus.co.uk

Really good write up, nicely done!

Hello Martin

Thank you for getting in touch and thank you also for producing an excellent website.

I thought it would be useful to give a quote from the 2017 Lorenz book by Jerry Roberts.

“How long did it take to break a message by hand or machine?

Many people do not understand what it was that Colossus did. Many think that Colossus did the whole process and there was a lot of misunderstanding about how long it took to break a message compared to the hand-breaking method. Some people think Colossus did the whole process of decryption and that there was no need for human code breakers once Colossus was introduced.

Tony Sale, a volunteer at Bletchley Park, used to say that we usually took 4 – 6 days by hand, but other commentators have said that it took nearer 4 – 6 weeks. Neither of these is correct. I have great respect for Tony; he was a remarkable man and a fine engineer. His great contribution to Bletchley Park was leading his team to reconstruct a Colossus …

My recollection in the last year of the war was that, with the assistance of machines, I broke between 7 and 12 message daily and the machine took anything from 3 – 8 hours to produce the de-chi which was faster than by hand. The machines allowed us to cope with this growth in volume …”

I will certainly visit your website to try the virtual Enigma in celebration of Alan Turing’s birthday of 23 June.

Chris

An excellent vignette into an important period of the modern world.

I always talk about those elements of Alan Turings life that centre around he is most likely to have had a form of autism. Which helped break and decipher the codes. Autism is still something that is not fully understood, of which geniuses emerge, and of which is often still discriminated against. Something we should improve in the future.

Dave

Thank you for your kind comment about the article.

I understand that there is a wide spectrum of autism.

In Captain Jerry Roberts’ book entitled, “Lorenz” of 2017, is an observation:

“I used to see Allan Turing from time to time at the park: a man of medium height, 29 at the time, dressed in a sports jacket and rather baggy grey trousers (a bit like mine). He would walk along the corridor in one of the huts with his gaze averted from other people, looking at the bottom of the wall and flicking the wall with his fingers. While not very comfortable in company and certainly a shy man, he was on very good terms and sociable with other mathematicians of his kind. You would never guess that this was the most influential man in Europe at that particular time”.

We should be pleased that Bletchley Park did not discriminate against those who are different from what is referred to as the established norm and that their considerable talents and intellect could be utilised.

Also of interest are comments from Lewis Powel Jnr, an American who served as the ULTRA officer on General Carl Spaatz’s United States Strategic Air Forces staff and later become a United States Supreme Court Judge. He was interviewed by academics, Drs Putney and Kohn, in 1987.

“Putney: Did you meet Alan Turing?

Powell: I don’t remember him by name.

Putney: One of the inventors of the BOMBE?

Powell: Oh, yes, right. I did meet him and most of the ULTRA family during the Bletchley training.

Kohn: Turing was a mathematician.

Powell: Exactly. He was a don at Cambridge. The word “brilliant” fails to reflect his genius.

Kohn: Yes, I believe he was, apparently, quite an unusual, eccentric character.

Powell: There was more than one, I’ll tell you.

Putney: So you saw everything there was to see at Bletchley?

Powell: I did, at least so far as I know, see everything that had to do with my future duties…

…They had a big cafeteria in the main building, and the ULTRA people used that with the other people, and very few people wore uniforms, and rank did not make much difference at all. It was a very stimulating place to be, obviously, so much so that it gave those of us who were fortunate enough to have that training an enormous advantage.”

Chris

Thank you Chris, This is insightful, and useful, it says a lot about our past.

Great stuff as usual, Chris. Just a few quick random thoughts arising from this. Bletchley Park was an example of great teamwork being effective. You might ask why the German side could not do the same thing. My recent researches point to Germany being anything but a united camp, particularly in the latter stages of the War as internal rivalries boiled up. As for the Russian side, their approach was usually mandated on winning over deeply seated spies and double agents and this continued for some years after the war. However, they also had the scientific knowledge to follow on and develop code systems and that seems to have happened.

There are so many things that happened during WWII that turned the tide, often by chance. One data set that often springs to mind for more than one reason are the weather readings from the woman in Mayo on the West Coast of Ireland that put D-Day back by one day. My other reason for remembering this is that my birthday is on the 6th of June.

Do I see a book or a more extensive piece of some kind emerging from this?

William

William

Thank you for your input and a belated Happy Birthday for 6th June. My late uncle had the same birthday and I was told he spent his D day as an eighteen year old, flying a patrol over the Humber Estuary, Yorkshire, in a Tiger Moth.

The weather forecasts for launching D Day were critical and Group Captain James Stagg RAF was the Chief Meteorological Officer responsible for briefing Eisenhower. I now know Ireland had a key role in James Stagg’s advice.

I have found this on the web:

“On June 3, 1944, Irish Coast Guardsman and Blacksod lighthouse keeper Ted Sweeney and his wife Maureen delivered a weather forecast by telephone from Co Mayo’s most westerly point. The report convinced General Dwight D Eisenhower to delay the D-Day invasion for 24 hours, potentially averting a military disaster and changing the course of World War II.

Although separate observations were taken at various locations by Royal Air Force, Royal Navy and the United States Army Air Force meteorologists, an accurate forecast from the Irish Meteorological Service, based on observations from Blacksod on Mullet peninsula would be the most important. Despite the country’s neutrality during the war, Ireland continued to send meteorological reports to Britain under an arrangement which had been agreed upon since Independence.”

Do I see any follow up to this Ultra story? Perhaps not as I do not really see myself as an author. The next challenge I am setting for myself is to take some decent photographs in Dedham Vale, “Constable Country”, which is where John Constable grew up. Many of his famous paintings such as the Hay Wain are of that area. As I live only a few miles away, I hope to capture the open Suffolk skies with their particular cloud formations.

Chris

You might be interested to see – or read – David Haig’s play ‘Pressure’ ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pressure_(play) ) which is about exactly what you describe ..with a bit of artistic licence: the wait to see what the weather would be for the projected D-Day landings.

I can’t remember where we saw it; according to Wikipedia it was on at Richmond and the Ambassador’s ..so that must have been where we saw it (though the Ambassadors seems to have a small stage, and I seem to remember it being on a much wider stage ..must depend on where you’re sitting!)

I was surprised that David Haig – usually known for comedies – would (a) have written this serious, tense work, and (b) would take the lead in it! Well worth searching out if you can find it.

Fascinating article that reveals one aspect of our rich history to many of us who might not have known about it.

You can also sense the urgency of the situation because in Mike’s photo that woman still has her curlers in!

Stephen

Thank you. I’m glad you found the article fascinating.

Perhaps the caption for the female naval officer with her curlers still in should have been; ”I’m sorry I overslept” rather than “Please listen”.

Chris

Wonderful article and photos. The stress of combat on the front line can somewhat be relieved by shooting back at SOB’s, but these brave folks must have had nerves and constitutions and minds of steel. I can only imagine how much unreal pressure was on these Heroes and heroines! Thank you

John,

Thank you.

Roy Jenkins who was a prominent British politician, a former President of the European Commission and Chancellor of the University of Oxford, died in 2003. In the war he was part of the Testery team at Bletchley. Captain Jerry Roberts, a shift leader, said that Roy Jenkins had no knowledge of German and no knack of code breaking. This made it frustrating for Roy when he tried to tackle a message.

Roy gave his recollections of his own feelings in his autobiography, ‘A Life at the Centre’:

“I went to a dismal breakfast having played with a dozen or more messages and completely failed with all of them. It was a most frustrating mental experience I have ever had, particularly as that act of trying almost physically hurt one’s brain, which became distinctly raw if it was not relieved by the catharsis of achievement”.

He in the Testery later became a useful “wheel setter” rather than a, “code breaker”.

John you are right in realising the unreal pressures on the staff at Bletchley Park.

Chris

A great read to start the weekend.

Thank you

Jean

Jean, thank you.

Mike provided me with initial encouragement and quality photographs.

I could go into great detail about Ultra with its role in D day and the Battle of Normandy but perhaps a better comment would be to inform people about the new British Normandy Memorial at Ver-sur-Mer, Calvados, which was officially opened on 6th June this year. Not that far from you I believe.

The British Normandy Memorial records the names of the 22,442 servicemen and women under British command who fell on D-Day and during the Battle of Normandy in the summer of 1944. This includes people from more than 30 different countries. Inscribed in stone, their names have never, until now, been brought together. The site also includes a French Memorial, dedicated to the memory of French civilians who died during this time.

Google “British Normandy Trust”.

To me, the memorial itself and its location are truly stunning and very moving.

Chris

Maybe Jean can get his GR focused on the memorial and the surrounding area…

Much appreciated, thank you – a fascinating read.

Richard,

Thank you. I’m glad you found the article fascinating.

Chris

A fascinating article Chris with enlightening illustrations from yourself and Mike. I appreciated the amount of research and high level of scholarship that went into its creation. I think it will stand alone as a valuable reference on the work of Bletchley Park and deserves an audience far beyond the readership of the blog. One to be proud of.

Kevin,

Thank you very much for your kind comments and I’m pleased you thought that it was a high level of scholarship. I enjoyed doing the research for the article. It certainly made lockdown a little more tolerable.

Chris